Chest Pain: No Second Chances

This case perfectly illustrates the risks involved in chest pain work-ups, especially when discharging patients. Whenever a patient is discharged from the ED, the physician must consider what will happen to the patient if their assessment is wrong. What will happen if their condition unexpectedly worsens? A good EM doctor will equip their patient with knowledge that will ensure they return to the ED if needed.

In many cases, if a patient’s condition does worsen, they will decompensate over hours or days. This relatively long period gives the patient time to realize they are feeling worse, recall the return precautions they were given, and make it safely back to the ED for reassessment. This time period is the buffer that protects the patient (and physician) from bad outcomes.

Unfortunately, for patients with acute coronary syndrome, this buffer time can be essentially zero. A chest pain patient who actually is having an ischemic event can go from walking, talking (or making coffee) to pulseless in a matter of several seconds. They feel exactly the same from their ED discharge right up until they experience sudden death. There is no prolonged worsening of symptoms that allows for safe return back to the ED.

A patient with a UTI that progresses to sepsis may feel worse over several hours. A patient with an acute coronary syndrome drops dead in seconds.

An asthmatic will feel their breathing worsen over time. A patient with an ischemic heart can go pulseless in an instant.

Someone in an accident with a missed liver laceration will slowly feel more lightheaded and weak as they bleed. The person sent home with chest pain can go into V tach with no warning.

The point here is obvious. Chest pain patients are unique because there may be no second chance after discharge.

Nitroglycerin

The physician was falsely assured by the patient’s lack of improvement after being given nitroglycerin. He states in his deposition that it was used as a “diagnostic and therapeutic test”. This is a gross misunderstanding that can easily lead down a path of false reassurance. To be clear, improvement with nitroglycerin does not rule in acute coronary syndrome, nor does a lack of response rule out acute coronary syndrome.

This has been shown numerous times in numerous studies, including this paper in which the authors conclude “relief of pain after nitroglycerin treatment does not predict active coronary artery disease and should not be used to guide diagnosis”.

The attorney asks a very leading question and gets the physician to agree that multiple administrations of nitroglycerin would be needed to rule in cardiac causes of chest pain. He is implying that the physician’s use of nitroglycerin was inappropriate because he did not test her response to nitroglycerin multiple times. This is also erroneous and illustrates the incompetence of both parties involved.

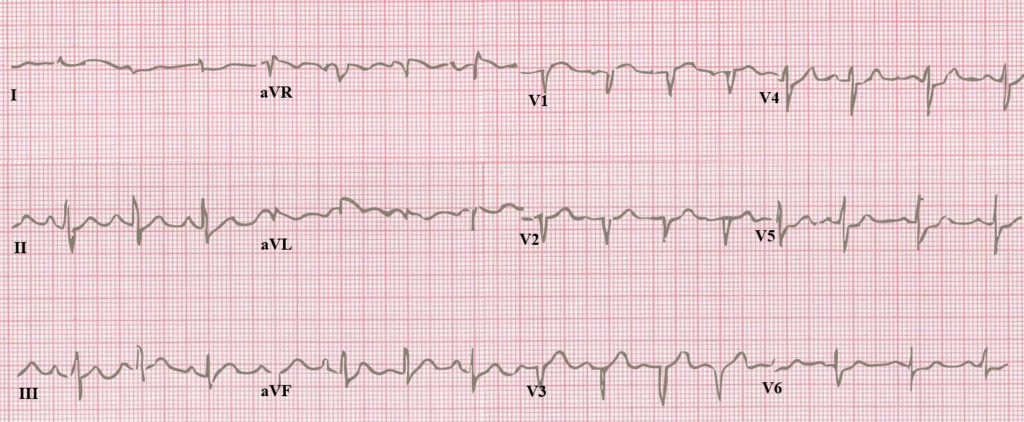

Automated EKG Interpretation

There is a famous phrase from Amal Mattu about plaintiff’s attorneys and automated EKG interpretation that applies perfectly to this case:

Plaintiff’s attorneys have no idea how to read an EKG. Therefore they rely on the laughably bad EKG interpretations that are generally ignored by every clinician who has more than 10 minutes of basic EKG education.

It is painful to read the deposition of the doctor and hear him have to explain his decisions in light of the automated EKG interpretation. While this physician’s workup left something to be desired, his lack of attention to the automated EKG interpretation is not an area of concern.

Preventing these interpretations from printing on the top of every EKG would be a wise idea to help avoid misinterpretations by reviewers with no medical training.

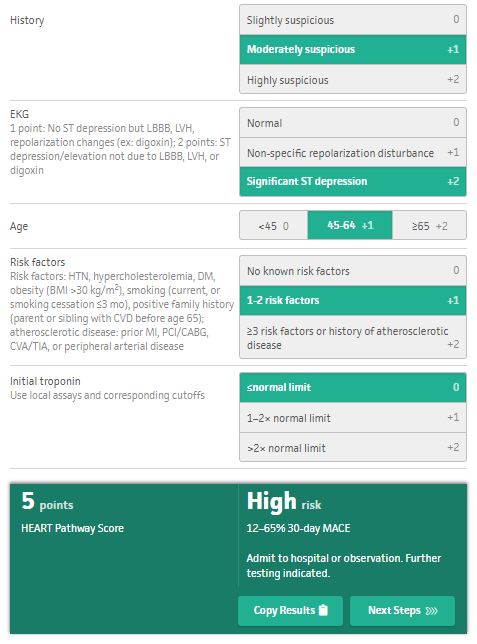

HEART score

Over the past few years, the HEART score has gained widespread adoption among EM doctors for the assessment of chest pain patients. It’s most common use is to identify low risk patients who can safely be discharged with outpatient follow-up, rather than hospital observation and more aggressive hospital-based testing. While it was not being extensive use at the time of this case (2011), it is an excellent opportunity to apply it.

Applying the HEART score for this case gives a score of at least 5.

This is a charitable application of the HEART score. It could be argued that her history was “highly suspicious”. She also had two additional risk factors identified at the university medical center: CVA in a relative and hypertension. These additions would have pushed her score as high as 7. Whether her true score was 5 or greater is irrelevant. She was not low risk and utilization of the HEART score could have helped inform the physician that discharge was not an appropriate decision.

Even for patients who are low risk (HEART score 3 or less), most EM physicians will repeat a second troponin. It is not entirely clear how much time lapsed between the start of her chest pain and the initial troponin. However, waiting for a second troponin would have given the physician a better chance to change course and prevent a catastrophic outcome.

Standard Chest Pain Workup

Aspirin is one of the few medications that can actually provide benefit to patients who may be having acute coronary syndrome. It is a standard practice that if a patient is being worked up for chest pain, they should probably be given 324mg aspirin. In this case, no aspirin was given.

Additionally, a chest x-ray is usually indicated in the workup of a chest pain patient. It is not clear if one was obtained in this case. Not all cases of chest pain are from a cardiac cause. In fact, the vast majority are not cardiac in nature. Pursuing a workup for a broad differential including pneumonia and pneumothorax is a wise idea, and a chest x-ray will help identify these alternative causes.

Chest Pain Discharge Planning

Assume for a moment that this patient was low risk based on her HEART score. Generally speaking, these patients are referred for rapid outpatient follow-up. While there is debate about the utility of a stress test in these patients (over-utilization in low probability populations has given stress tests poor test characteristics), most patients will receive a stress test.

The physician did not seem to have a plan for the patient’s follow-up. The idea that this occurred in a “small town” and therefore the patient would return if her condition worsened is faulty. The size of a town’s populace does not alter cardiac pathophysiology. The discharge planning was admittedly difficult due to the patient being on vacation and not having a local primary care doctor to see, but these issues can be overcome.

Eager to Leave

In the doctor’s deposition (page 52), he notes that her desire to go home was a factor in his willingness to discharge her.

Most patients want to leave the Emergency Department. It is generally not a pleasant place and almost no one wants to be in the ED. The few people who do want to be in the ED are well-known to staff and have deep-seated psychological issues. A desire to leave is not a particularly remarkable factor.

Judging the safety of a discharge by the patient’s eagerness to leave is often a mistake. Their desire to go back home is generally not a reliable indicator, nor is it protective.

Mental Errors

The doctor was faced with several possible explanations for this patient’s chest pain. He knew this could be a cardiac event, or it could be a sunburn. He decided the most benign explanation was correct and the patient paid for it with her life. ED physicians think from a perspective that always considers the worst-case scenario first, even if it is extremely rare. This is a marked difference from many other specialties of medicine, that often consider the most likely explanation first.

Rather than pursue a full workup for emergency causes of chest pain, the doctor performed only part of the workup, and then decided to assume the most benign possible explanation. While positive thinking is an admirable approach to life, assuming the best for our patients is a fragile approach to emergency medical care.

A senior physician with multiple decades of experience described this faulty approach as “wishing our patients well”. Rather than doing the difficult work of looking for an underlying emergency, we perform mental gymnastics to find the most benign possible explanation for every piece of information that faces us.

Don’t wish your patients well. Do the work to uncover the reality of their presentation.

In this next page we will review the documentation in the doctor’s chart.